This is a simple idea: let the images speak, since (for once!) we have plenty of them. Immediately, a series of problems arise: do images speak? And if they do speak, what can they tell us? A hasty interpretation can often lead astray, since rock carvings, like all the artistic languages, have a great charge of ambiguity.

The ancient inhabitants of Valcamonica carved on the rocks the themes and symbols of their culture, selecting subjects according to criteria that elude us today and are almost impossible to reconstruct, so it is good to be cautious and to be aware from the start that excessively naive reconstructions will leave room for enormous doubts.

For the images to speak – and this is true for every people and every civilization – it is necessary to reconstruct what functions are attributed to them, what cultural horizons generated them, and what momentum sustained a work that continued for several millennia, producing the great heritage of Prehistory (and beyond) in Valcamonica.

Orants

Depictions of schematic anthropomorphs with raised arms and spread legs, generally attributed to the Neolithic period, but destined to have good fortune even later: they were depicted until the Metal Ages, with progressive stylistic modifications and inserted in different contexts. Some orants have differentiating elements, such as exceptionally large hands or feet, pronounced sex (both male and female), and larger proportions than other human figures next to them. In the latter cases, they could represent individuals of special prominence within the social group, if not even spirits endowed with exceptional powers or attributes. The debate over the exact chronological attribution of these figures is still lively and heated among experts.

It is possible to admire orants in almost every site in the Reserve, with the most classic examples in Foppe di Nadro (Rocks 1 and 21) and Campanine di Cimbergo (Rock 7).

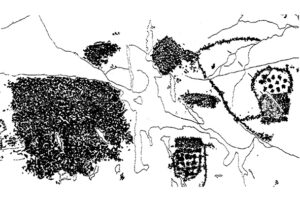

“Mappiformi” (map-like figures)

Some authors interpret these compositions as depictions of actual agricultural territories (cultivated fields? Settlements? Livestock pens?); others, more cautiously, as an abstraction of the concept of “territory.” The earliest typology of this subject is called “macula” (Latin for “little spot”), consisting of more or less regular areas that were entirely hammered; later, they were replaced first by double rectangle figures and became more and more articulated, up to complex geometric compositions that also include cupmarks and gullies. Again, the chronological attribution is uncertain, ranging from the final phase of the Neolithic to the Bronze Age. We can see these engravings on many rocks in the Reserve: some examples can be found in Foppe di Nadro, but the greatest concentration is in Paspardo (in the areas called Vite-Deria and ‘Al de Plaha).

Ploughing scenes

The theme of ritual ploughing first appeared in the final phase of the Neolithic period and continued to be engraved well into the Iron Age, where it comes into play in the creation of the boundaries of newly founded cities (as attested, for example, by the legend about Rome), or in awakening the fruitful and sapiential power of the earth (the Etruscans attributed the ability to unveil all knowledge about the universe to Tages, a supernatural being that emerged from the newly ploughed furrow). Inside the Reserve, Rock 8 in Campanine may depict the oldest ploughing scene in Europe: two pairs of “bucranes” (Latin for “bull skulls”, the earliest representation of bovines) harnessed to the plough, probably referable to the mid-4th millennium BCE. Other, more recent examples can be found on the rocks of Foppe di Nadro and Campanine.

Weapons

A typical subject of the Metal Ages: starting from the Copper Age (when man learned the first rudiments of metallurgy), weapons became tools and symbols of military power, but also a very important source of trade and accumulation of goods. Indeed, it was with the arrival of metal that the symbolic, economic, and social importance of the “weapon” object grew: firstly depicted on statue-stelae, then on rock surfaces, and finally wielded by the countless depictions of Iron Age warriors (1st millennium BCE).

Throughout the long artistic period in Valcamonica, the abundance of axes, daggers and halberds first, and spears, swords, helmets and shields later describe a warrior and masculine universe. Weapons are very important to date rock art engravings: by examining and comparing their shapes with excavated objects (mostly from burial sites), archaeologists have been able to establish the chronological sequence of the rock engravings.

It is possible to admire valuable compositions of weapons in almost all the visiting areas of the Reserve (Foppe di Nadro, with its Rock 4, Campanine di Cimbergo, and Paspardo).

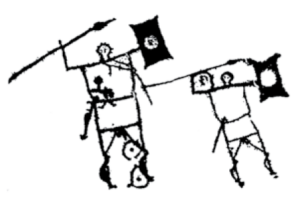

Warriors

The dominant theme of the engravings made from late Bronze Age throughout the Iron Age is undoubtedly the warrior: depicted alone, while duelling, grouped in ranks, with or without his weapons in full view. Warriors are often depicted in close combat, bearing weapons of quite different types (such as swords, spears, axes, shields, helmets). The ones depicted on the rocks are probably ritual duels, particularly evident in the Zurla pair (site inside the Reserve but not open to the public), in which the duelling figures show “special” panoplies and seem to mimic a dance, or on Rock 6 in Foppe di Nadro, featuring a double pair of duelists (the first using weapons, the second boxing).

The duel in Italic antiquity was often charged with social and religious meanings, as in the case of the judicial duel (a clash between two champions to avoided the one of the armies they belonged to), or the contests or games organized to honor the dead in funeral ceremonies. It is not excluded that those in Valcamonica could be the mythological or legendary depiction of an epic duel between two ancestors, heroes, or gods.

A noteworthy category among these figures are the large outlined warriors from Paspardo, 90 to 140 cm tall, with the faces depicted in profile and sex and weapons clearly in view (Rock 4 from In Vall and rock 5 from Dos Sottolaiolo).

Horses and horsemen

Ridden horses make their appearance in the iconographic repertoire of rock engravings only during the Iron Age. In antiquity the horse possessed not only a great economic value, but also – and above all – an ideological and symbolic one, so owning one or multiple horses must have characterized different ranks within the social hierarchy also in Valcamonica.

In particular, the figure of a large horse with a rider and his squire (Rock 27 in Foppe di Nadro) stands out, testifying to the extraordinary importance attributed to the mount during the Iron Age. Moreover, it also seems to highlight a precise differentiation of social roles in the distinction between the rider – armed with shield and spear (perhaps a Camunian princeps?) – and the “squire,” drawn in smaller proportions while on foot, driving the steed and bearing the rider’s spear.

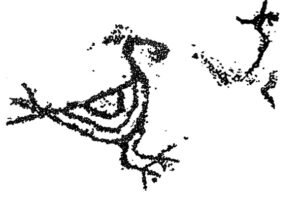

Birds

Depictions of birds – mostly waterfowl, corvids, and galliforms – bear strong symbolic values among many ancient cultures. In some emblematic cases, waterfowl become mounts of armed figures or – transformed into an ornithomorphic boat-like pattern – “carry” short inscriptions, written in the local alphabet (the so-called “Camunian alphabet,” a variation of the North Etruscan one). About this subject, it is important to mention the exceptional concentration of waterfowl on Rock 7 in Foppe di Nadro, and the beautiful giant wader on Rock 49 in Campanine di Cimbergo.

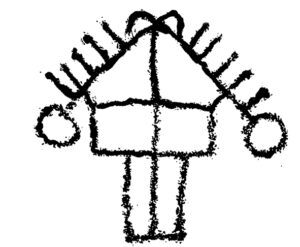

Huts

Depictions of huts or buildings are among the dearest themes to Camunian artists already in the Early Iron Age (10th-7th centuries BCE) and are distinguished by an extreme typological variety: no two “huts” have the exact same structure, all of them have at least a detail differentiating them from the rest.

Researchers propose two main interpretative possibilities: on the one hand, the Camunian “huts” are considered as the depiction of real constructions (stilts or barns, raised from the ground with piles); on the other, the many “impossible” depictions could be related to Tuscan-Latial cinerary urns and, more broadly, to the metaphor of the house as the eternal home of the deceased. This type of depiction is extremely widespread on the rocks of the Reserve, particularly in Foppe di Nadro and Campanine di Cimbergo.

Camunian Roses

Perhaps the most famous symbol of Valcamonica (which also became the official symbol of the Region of Lombardy in 1975), the Camunian Rose still constitutes a great enigma. Its presence in many regions of Europe, even very far apart (from Portugal to Sweden), allows us to assert that it is a symbol of continental origin, probably born in the Bronze Age but that became characteristic of the Iron Age. Many hypotheses have been made on its meaning, from solar symbol to musical instrument; recently, some scholars have speculated that the Camunian Rose may be connected to a feminine symbolism. Paspardo boasts the highest concentration of Camunian Roses in the entire Valcamonica (on the trails open to the public alone, we recall those of ‘Al de Plaha and Dos Sottolaiolo); another very famous depction is on Rock 24 in Foppe di Nadro.

Labyrinths

Labyrinth figures quintessentially symbolize a complex and obstacle-studded path that leads to a transformation in those who follow it. The “Cretan-type” labyrinth seems to refer to the cultural influences from the Mediterranean area, mediated by the Etruscans, and is thus related to rites of passage (such as birth, puberty, marriage, etc.). A beautiful labyrinth is engraved on Rock 1 in Campanine di Cimbergo.

Writings

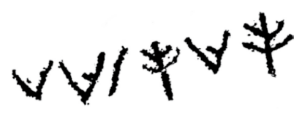

Around the 5th century BCE, an alphabet (so-called “Camunian alphabet,” also knwon as “Sondrio alphabet”) appears in Valcamonica: it clearly has a North Etruscan origin, but it was adapted to the phonetic needs of a (possibly) Rhaetic language. The two distinctive features of this alphabet are the upside-down letter “A” and the sapling-shaped letter “Z.” The inscriptions (probably names) do not replace the engraved figures, but fit seamlessly into the engreved contexts, sometimes with significant associations (ornithomorphic boats, huts, warriors…) that seem to suggest a funerary significance.

The greatest concentration of this subject is in Foppe di Nadro, where we recall the epigraph stating “ZAZIAU” on Rock 23 and the graffiti of the entire alphabet on Rock 24. Particularly notewortht is also the Latin inscription “SAX SECO” (lit., “I engrave the rock”) on Rock 60 in Foppe di Nadro.